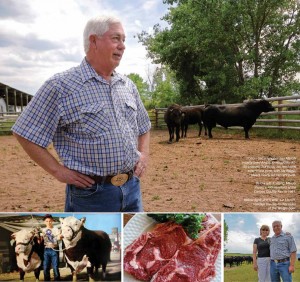

Thinly veiled behind a cloud of dust, he stands a paragon of masculinity: Angus Bull No. 395 — a 2,900-pound package of traffic-stopping muscle and testosterone.

Flanking him on either side, Bull No. 161 and Bull No. 175 — full-blooded Japanese Wagyu, both. On first appearance they are far less formidable, but in truth are worth twice the price per pound.

In the paddock beyond, cows and heifers form a concert of eyes that peer between weathered fence boards at the knotted sinew. In unison, the three square their shoulders, as Bull No. 395 settles into a stalwart stance that rocks a chunky brisket to and fro.

This is beef at its finest. This is Marchi Angus Ranch.

In the kitchen of his home, perched atop a cliff lording high above the swirling rapids of the Flathead River, Poison cattle rancher Jon March’ lugs a mammoth coffee table book to the kitchen’s center island.

It’s the sort of epic tome one might purposely lay across a whole lap to admire stark black-and-white images of Yosemite, shot by Ansel Adams, or delight in the frame-by-frame shock of Helmut Newton’s iconic portraiture.

But no earthly monument, nor lean and hungry model, graces these pages. Called simply “Breeds of Cattle,” this 20-pound volume is chock full of the world’s bovine breeds.

Marchi cracks the back of the book’s thick spine and leafs easily to a section with dog-eared pages, then points a worn linger at the Japanese Wagyu breed. Stout. Compact. Horned. Black or red in color. The bull on this page could be the spilling image of either 161 or 175— take your pick.

Inked in record books as the seventh-ever member of the American Wagyu Association, Marchi is part of history in the making — one of a cadre of ranchers squiring this fledgling breed to the forefront of U.S. and Montana agri-business.

For years, he grazed herds of hearty Scottish Angus on live ranches spanning 2,000 irrigated acres. But since 1996, when Marchi began breeding Wagyu into his line with semen procured from Washington State University, Japanese Wagyu have shared this landscape.

Marchi initially bred Angus to Wagyu for 50-50 crosses. Today, his herd runs even more pure — with papered Wagyu steers averaging 15/16ths (or 93.75 percent) pure on slaughter day.

For cattle to be considered Wagyu, both the American Wagyu Association and the U.S. Department of Agriculture say they must be at least 50 percent crosses.

“Meat from 50-50 crosses can he erratic, though,” says Marchi. Even with the stability of the Angus breed as an able cross, “most would still only offer the quality of Angus beef — not Wagyu.”

An old faded photograph in the Marchi home shows a young Jon standing next to a showmanship trophy, holding on to the end of a halter rope attached to a large red Hereford. He is beaming. It is the 1961 Carbon County Fair — a time when his family owned cattle in Red Lodge.

Marchi hasn’t owned a red Hereford steer since. Nor any other colored breed, for that matter. A fascination for Black Angus since 1974, and for Wagyu since 1996, means he now only bets on black.

Beyond color, distinctions between the Angus and Wauyu breeds are most noticeable at head’s crown: Angus bulls don’t have horns. Both bulls and heifers in the Wagyu breed do.

“Initially, there was a lot of resistance to the breed in the U.S. because of aesthetics,” he says. “People thought they looked like a dairy cow with horns.”

But never mind how this breed looks. In the end, it’s all about taste.

Just beyond that 20-pound picture book, executive chef Zach Bernheim of Kalispell’s North Bay Grille forms Wagyu beef patties in the Marchi’s ranch-house kitchen. Once removed from a sizzling cast iron pan. these palm-sized chunks of ground beef will barely be contained by miniature slider buns.

Just beyond that 20-pound picture book, executive chef Zach Bernheim of Kalispell’s North Bay Grille forms Wagyu beef patties in the Marchi’s ranch-house kitchen. Once removed from a sizzling cast iron pan. these palm-sized chunks of ground beef will barely be contained by miniature slider buns.

A few feet farther, a pair of perfectly marbled ribeye steaks sit on a platter awaiting the grill. Marchi and Bernheim have set them out to demonstrate the intricately marbled fat laced throughout, and point to the fact that no adipose has been trimmed from its borders; it can all be found within the steaks’ borders.

Chef Bernheim says top cuts of Waayu are so tender they can be sliced through with fork alone, and that the quality of the beef is so high its grading scale surpasses regular USDA standards.

“On a scale of one to 12, Wagyu will always grade higher than the best prime-graded beef by between two and seven points,” he says of the breed that also garners distinctions from “black” to “platinum.”

According to the USDA website, for a Wagyu steer to win a grade of 12 would be rare, but a routinely good subject will probably score a 10.

“As a frame of reference, a great prime grading for regular beef is around a six,” Marchi adds.

Most people don’t associate the Wagyu name with Kobe-style beef. It’s a bit Ike the Champagne region of France and its sparkling wines. Produced outside the region. no sparkling wine can legally be called champagne, yet most of us classify any and all bubbly as exactly that.

No matter how you slice it, whether Kobe-style beef is found in Japan, or in the U.S., it all originates with the Wagyu breed, says Marchi. “It’s the same beef.”

Still, the lore that surrounds Japan’s Kobe-style beef grows broader by the decade.

Americans unfamiliar with the Wagyu breed sit rapt with wonder over how they are supposedly raised: It is said that Kobe beef breeds are fed an exclusive diet of beer mash, and are rubbed down daily with full-body massages, like princes and kings.

“Well, that’s not exactly true,” Marchi says.

Cattle are massaged with large wooden rollers, and have tenders who are assigned 10 steers each, he says, but that’s to oversee their well-being in extreme confinement.

Tenders with rollers keep blood flowing and watch over an investment that barely has wiggle room, according to Marchi. So special handling owes more to land scarcity and exorbitant prices per acre — where herds don’t have the luxury of grazing like Montana cattle — as much to the mistaken belief that confinement will net a more tender steak.

It also owes to the reverence the Asian country has for what they call a “national treasure.”

But one thing is true: Even Marchi’s herd enjoys a little beer now and then — thanks to mash procured locally from Big Sky Brewing.

As for the Japanese Wagyu, less natural forage (grass and alfalfa) necessitates a diet higher in the byproduct grain mash. Waayu horn here have greater access to forage and are fed a smaller percentage of mash.

Two decades ago, a single 8-ounce I portion of Kobe beef hit tony restaurant plates at over 5100 — from Tokyo, to San Francisco, to New York.

These days, when a restaurant purchases a whole Wagyu steer, the Marchis are selling the meat at an average price of $4.50 to $5 per pound for around beef, and around $9 for primals. Primals may amount to 200 pounds, and ground heel to 300 pounds — making it a beefier purchase than most households care to endeavor.

But even in the current elevated beef market, the value for restaurants is good, and may rival grass-fed sources offering far less marbling, taste and tenderness.

North Bay Grille and beef purveyors at other line-dining spots in western Montana (The Raven, Blue Canyon, Tamarack Brewing Company, Ranch Club) continue to order and reorder M archi Wagyu, affirming it by default as a commodity well within grasp.

Zach Bern helm reasons that 350 pounds of ground Wagyu – as a vanguard to get people accustomed to it – means diners won’t be expected to plunk down S45 for a ribeye.

Zach Bern helm reasons that 350 pounds of ground Wagyu – as a vanguard to get people accustomed to it – means diners won’t be expected to plunk down S45 for a ribeye.

He says it also makes buying whole Wacyu a much more sustainable prospect, considering the restaurant might routinely go through 80 tenderloins and 20 ribeye steaks per week.

“At that rate, if I was serving nothing but premium cuts, Ed wipe out the Marchi herd in under a year,” Bernheim says.

Liz Marchi handles most of the day-to-day selling of the specialty marbled beef, ensuring first-time and returning customers get what they need and understand the benefits of the breed beyond marbling – such as the fact that Wagyu is higher in unsaturated fats, including Omega-6 and Omega-3 oils.

As founder of Frontier Angels – a group of accredited investors providing equity capital to early and mid-stage entrepreneurial companies – like any other business, she learned how this one worked from the ground up.

“Beginning with the simplest of curves – like the difference between a bull and a steer, and between a heifer and a cow,” she says laughing.

Then there was the hurdle of having been a longtime vegetarian when she met Jon in 2001.

By the time they married in 2006, her eating habits had changed.

“I enjoy the meat as much as he does now – home-raised meat is wonderful,” March’ says.

As abruptly as he took his stance, Bull No. 395 breaks formation first. The 10-minute steely-eyed standoff is over and he begins to mill the paddock with an edge of boredom. The others follow suit.

Jon Marchi says these three bulls will probably never end up on a plate. After all, they’ve got a lot of social oiling to do in this herd of 130 cows and maiden heifers.

Meanwhile, Bull No. 75 may not fare as well.

Recently castrated for repeatedly jumping a five-foot farm fence, he now stands docile behind a pack of cows – a massive shadow of rapidly diminishing muscle, marbling with fat by the minute.

Lori Grannis is a local food columnist and frequent contributor to Missoula magazine. She can be reached at 360-8788 or by e-mail at Ilgrannis@gmall.com.

Kurt Wilson is photography editor of the Missoulian. 1-k can be reached at 523-5244 or by email at kwilson missouliatz.com.